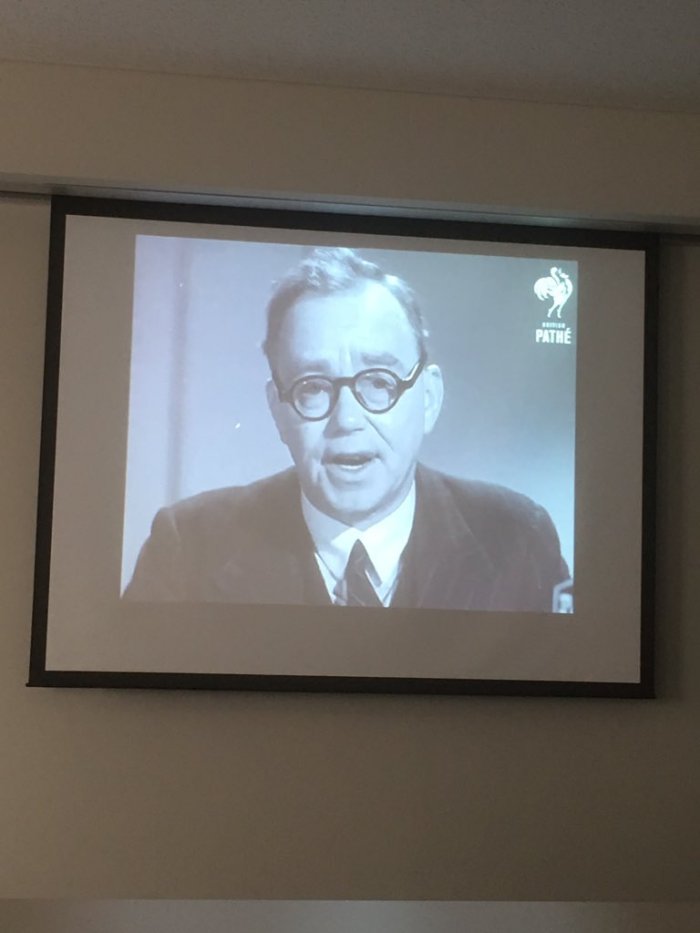

Arthur Horner, Communist leader of the NUM and a Welshman, speaks on east European immigration following the Second World War

In 2016, Brexiteers sought to make migrants from the former Soviet block countries of eastern Europe a scapegoat for economic woes. However, the story of when racism was last directed in the coalfield against ethnic groups from eastern Europe has largely been forgotten. Its forgetting testifies to the erasure of working-class intolerance when clearly connected with the politics of socialism and class, the hidden archaeology about which coalfield culture is in denial.

Stalin’s push at the end of the Second World War to the Adriatic and as far west as the Elbe led to a flood of political refugees from eastern Europe. Tens of thousands fled to Britain, many of whom who were employed in mines chronically undermanned following the end of the war.

We can pick up the subsequent debate about these outsiders in a four-minute film from 1947 broadcast under the title, ‘Pathe Industrial Survey No 7 – Mines Need DP Labour – A Reply from Wales’.

The film can be viewed here

The film opens with a short clip of the most powerful trade union leader of his generation, the Welshman, Arthur Horner, Communist leader of the National Union of Mineworkers, giving his view on whether ‘displaced persons’ from the east should be employed in British coalmines:

The coal crisis has produced a general appreciation of the fact that the British economy depends absolutely on a given quantity of coal. So that we are therefore forced to consider the employment of Poles and displaced persons. We now urge the authorities to provide wages and conditions which will attract free Britishers into Britain’s basic industry. Foreign labour can only be regarded as an emergency measure for a specific and limited purpose.

Horner’s broadcast is followed by vox pops with various miners, and what seems to be a semi-scripted staged meeting at the miner’s lodge at Penygraig in the Rhondda Valley. Here and elsewhere a variety of differing views ranging from the tolerant to the racist are presented, with nuanced intolerance claiming the centre ground.

Horner’s speech is given from a British viewpoint. Nevertheless, it contains key words which from a Welsh perspective, and for an understanding of racism as an expression of class unity in Wales, appear to be central. In particular, Horner’s term ‘Free Britishers’ is key. In ethnic relations, the term ‘Britisher’ and its synonyms have been used in Wales many times.

In the early twentieth century, massive immigration from England between 1880 and 1914 had created two ethnolinguistic groups in the coalfield. Here the term ‘Britisher’ was an important term because it effected unity across this ethnic divide. However, this unity could only be defined in opposition to an ‘Other’, inevitably a coalminer from some part of the European continent, or war against Germany, or an imperial adventure. Thus at Abercraf and Ystradgynlais in the Swansea Valley, there were protests against Spanish miners who had moved to the area a little before the First World War. In a 1914 article, ‘Foreigners in the Anthracite District’, the socialist newspaper Llais Llafur (Voice of Labour), describes tension as being between ‘Welsh and English miners’ on the one hand and ‘foreign workers’ on the other. Here the Welsh and English are being united in the face of a foreign ‘other’. Scapegoating non-British immigrants in a coalfield in which there were substantial tensions between two British nationalities helped forge working-class unity.

Can something similar be seen at work in the 2016 Brexit referendum? Were tensions between various British nationalities in the UK somehow placated by a working-class British identity which pitches the ‘Britisher’ against the foreigner? In this context, the Brexit vote is a response to the SNP and the Scottish Independence Referendum of 2014.

In rural Wales today, where a similar ethnolinguistic divide exists to that in the coalfield in the early twentieth century, the ideology of the ‘Britisher’ might effect a similar unity. Anglesey was the home of the leader of Ukip in Wales, the Englishman Nathan Gill. He defined himself as local by appeal to a civic identity extended to him as a Britisher sharing Britishness with other Britishers in Wales. Ethnic tensions between English and Welsh are assuaged. This is realised by projecting fear of the Other onto the island’s tiny ‘immigrant’ eastern European population.

We cannot forget that working-class Welsh culture discriminated against other minorities too. The coalfield had a very poor record on gender equality. Nearly all elected political representatives and other leading figures in society, including within trade unions of course, were men. The coalfield was also deeply reactionary in its political treatment of the Welsh language. Although Welsh speakers were formerly a majority, and latterly a significant minority, in the coalfield throughout the twentieth century, there was no form of bilingualism in public life. The Welsh language threatened the unity of the working-class because it suggested that working-class culture was still open to cultural and linguistic divides. It is clearly significant that, in addition to antipathy towards immigrants, coalfield culture was not inclusive either of what might be termed internal cultural minorities.

It is Welsh socialism as an ideological construct which is largely responsible for this majoritarian intolerance. Socialism believed itself to be a universal creed. It was suspicious of difference. Majority culture (which was socialist) saw itself as inclusive and international which explains in part the reluctance to acknowledge racism and intolerance as a problem within coalfield culture.

The coalfield was thus poorly placed to be culturally receptive to the leftist arguments of the twenty-first century as regards respect for ethnic, linguistic, cultural, sexual and gender difference. Welsh-speaking Wales was relatively open to these messages because as a linguistic minority Welsh-speakers appeared to benefit from such rhetoric, and their intellectuals often justified calls for language rights on the basis of diversity. Cardiff, the capital city, was home to a university and other middle class institutions around which liberals and those who enjoyed a metropolitan lifestyle congregated. In this milieu, metropolitan forms of diversity were readily accepted because they had been designed within other similar metropolitan centres.

Of course there is no claim here to a particular morality pertaining to Welsh-speakers and others. We are merely talking about a construct, and how a politics of assimilation and exclusion presented as class loyalty played a peculiar ideological role in some areas of Wales. This happened in part because of an awareness of the residual bi-ethnic, bi-cultural and bilingual background of the population whose internal difference had to be overcome in the name of class unity. (Indeed, it is of great interest that some forms of nationalism in its fear of Welsh internal difference –especially the radical linguistic otherness of Welsh-speaking communities – merely takes up the baton of ‘unity’ which British class socialism puts down).

In the coalfield, working-class politics thus had a tendency to be expressed in terms of opposition to arguments for diversity. The Labour Party’s loss of a very safe constituency, Blaenau Gwent, in both the Welsh and British Parliaments to independent candidates on the issue of local opposition to gender quotas says much. Plaid Cymru’s failure to make headway in the coalfield because of the party’s perceived association with the Welsh language says something too. They are both sides of the same phenomenon.

Thus the coalfield vote for Brexit should not be regarded as wholly unexpected. Brexit cannot be dismissed as a transient phenomenon for ethnic protectionism has been an important and at times central element of coalfield culture for the best part of two centuries. It is part of a tradition of socialist resistance to the Other.

Reactionary thought, deeply ingrained in coalfield culture, reflects the claims of a particularist culture (male, white, British, anglophone) to pretensions of universality. It has done this to the detriment of other cultural formations. It is the peculiar development of progressive thought within a unified working-class which has permitted the development in Wales of this reactionary universalism.

SB